We’ve all seen the movie. The camera opens above Dodge city, standing like a dusty relic in the desert. Shots are fired. A woman screams. A body lies in the street, blood soaking into the dry dirt road. The black hat stands over his victim, an evil sneer across his face. He spits tobacco on the body and leers at the onlookers. He’s not afraid of all the witnesses. It’s clear, he and the vicious men like him own this town. He can do what he wants and there’s no one bad ass enough to stop him.

Until there is. The soundtrack opens to a melancholy whistle. A crow caws as a tumbleweed roles across the path of a weary horseman riding into town. He’s tall and gritty, his eyes slitted against the dusty wind. This is the new Marshal, and he’s not afraid to shoot first and ask questions later. By the end of the movie, having overcome great personal peril…and making love to the lovely daughter of the lowly grocer…he stands over the black hat now lying in the street, a bullet hole where his miserable heart once pound.

This image is an American archetype in the Hobbesian tradition. Society is riddled with crime and disorder until someone violent enough comes along and brings order at the barrel of a gun.

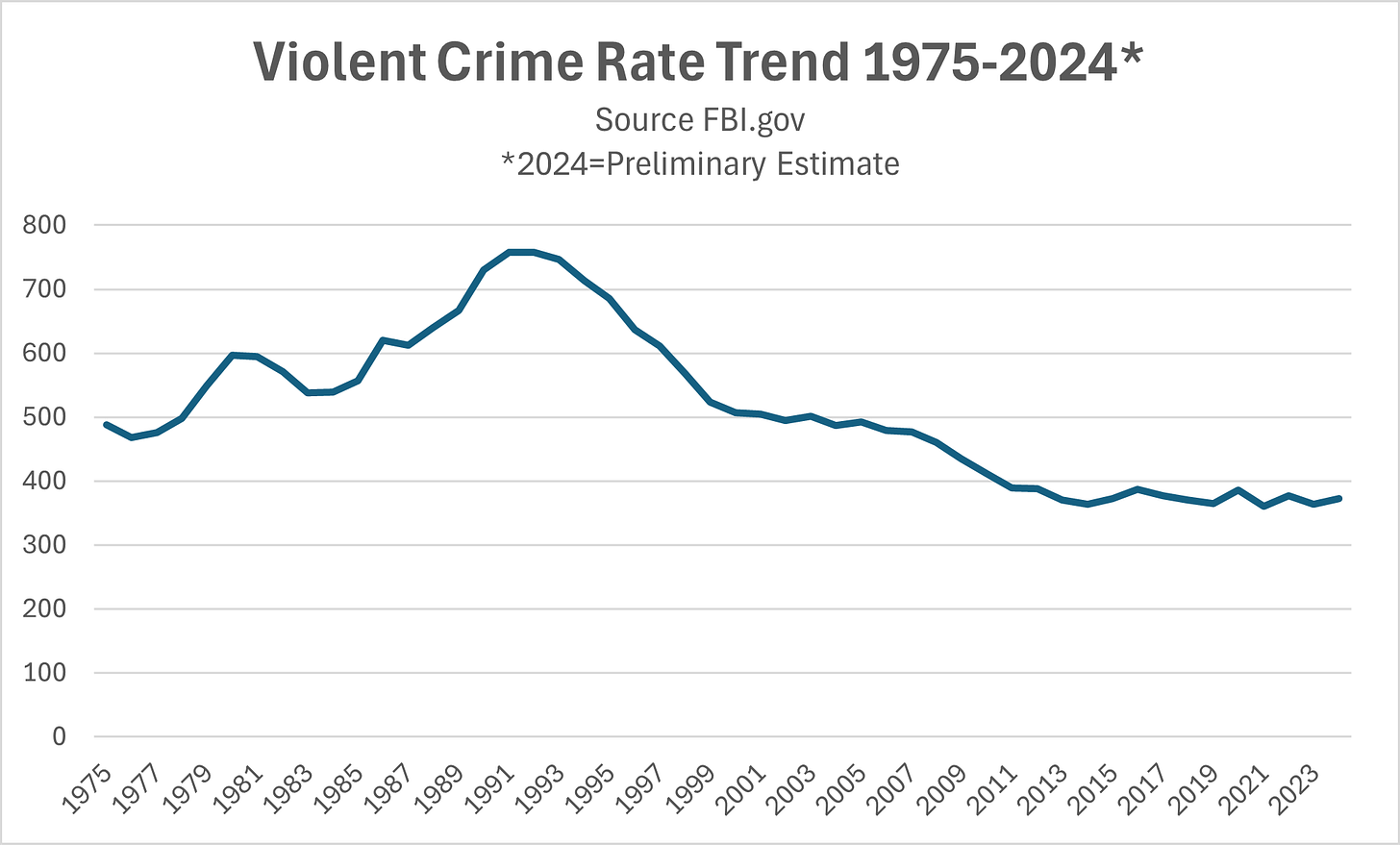

When I was a kid coming up in the 1980s, this archetype prevailed on our consciousness. You see, back then, crime really was rampant and seemed to be out of control. We feared that if trends continued we would be living in a world in which roving bands of psychopaths1 would control the streets and we would all be their prisoners. Our movies represented these fears, again with heroes who could match the psychopathic violence of the villains on more than a one-to-one ratio. Dirty Harry patrolled the streets with nothing more than a badge, a .45 Magnum (the most powerful handgun known to man) and a clear disdain for the suspect’s civil rights. Charles Bronson took revenge on those who victimized his family in Death Wish.

It was the same idea. There’s nothing we can do about this rampant crime but to outviolence the criminals.

Then, for some reason, somewhere in the early 90’s, crime peaked and then plunged. We’re not really sure why.2 One thing we do know. It wasn’t because a bunch of Dirty Harry’s went out with guns and cleaned up the towns.

Yet this seems to be the premise of MAGAs latest rationale justifying sending masked terror squads and the National Guard into DemocRAT cities. Remember, the original justification was to protect burly ICE agents in full tactical gear from the danger posed by angry soccer moms and hot-dog venders offended by the agency’s presence. But that made ICE sound pretty weeny if they couldn’t take care of themselves. After all, Paul Kersey didn’t need military back-up, and all he wore was leather jacket and a scowl!3

Since it’s impossible to claim that manly ICE agents need military back-up against a guy in a frog-suit, the rationale has shifted to the necessity of fighting crime. According to the Coifed Caligula, crime is running rampant in those DemocRAT cities…Portland is on fire! The big, tough guy in the Oval Office will send his big tough guy acolytes to get these countries out of control if the DemocRATS won’t.

It’s good politics. Crime is one of the only areas in which people trust the GOP.

It’s also a false paradigm.

It is likely that sending armed soldiers and para-military law enforcement into these urban areas will result in a small decrease in crime rates. That is assuming that they are actually stationed where the crimes take place. It turns out that crime, especially violent crime, in cities like Chicago are locally specific. They take place within relatively small community clusters in the city. Most of the city is as safe as anywhere else in the country. If the National Guard are not where the crimes are taking place, the results will be null.

The problem with this strategy is, of course, that a militarized response does not address the underlying causes of crime. Crime will drop for a time, then increase as those inclined to commit crimes learn where the weak links are. Then after some time the Guard will tighten up their weaknesses, there’ll be another drop, then a slight rise yet again. In the meantime, crimes may well increase in surrounding areas not guarded by the National Guard…um…that’s likely the white communities. Just sayin’.

That will be the pattern until the Guard are removed. At that point, crime will at the very least jump right back up to where it is now.4

The actual causes of crime are not being addressed.

The Causes of Crime

Policing in general, and especially the rise of militarized policing we have seen during my lifetime is a response to the perception of rising crime.5 Policing is an external social control. In other words, if I’m inclined to commit a crime, and I see a cop standing there, I might change my mind. On the other hand, I might simply decide to commit my crime where the cop isn’t standing. That’s the limitation of external social controls. Once they are no longer being applied, or once people find ways around them, they are no longer an effective tool for changing behavior. They may reduce the symptoms of an underlying social dysfunction, but policing never touches the the causes of the given dysfunction.

Fortunately, there’s a wide sociological literature on the causes of crime. We can trace sociological research into crime back over a hundred and thirty years to Emile Durkheim’s theory of anomie6. Anomie is the breakdown of norms and values resulting from rapid social change.

This kind of rapid social change was the focus of William Julius Wilson’s works around a hundred years later. Wilson pointed out that structural changes, like deindustrialization, and the out-migration of middle-class families, especially black middle-class families, from urban centers were direct causes of the social ills seen in black, urban communities throughout the nation. Loss of economic opportunity led to concentrated poverty, social isolation, and the cultural shifts in “street culture.”

Wilson’s observations of anomie in black communities resulting from diminished economic opportunity is confirmed by observations in white communities of the Rust Belt. When the factories close, poverty is concentrated. There’s outmigration of the middle-class. Small businesses and shops move out. There are fewer legitimate opportunities for achieving economic goals. Community members who may have served as role models in the past have moved away, and brought their social and economic networks with them.

An individual in such a community has only two options. They can pursue the acceptable economic goals of self-sustained prosperity only by leaving the community, or they can pursue illegitimate opportunities through criminal syndicates like gangs.7

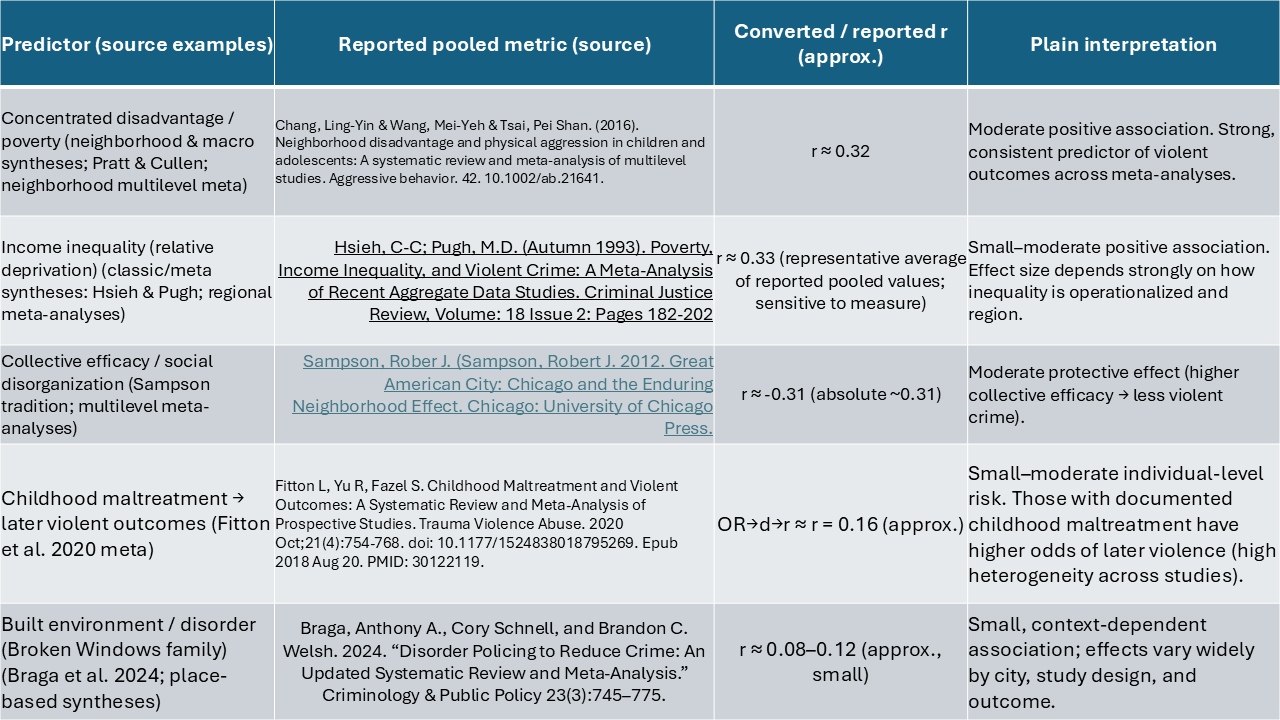

Fundamentally, the best predictor of crime is economic disparity. This conforms to the research. I used AI to seek out meta-analyses on the causes of violent crime8. Sure enough, the preponderance of the research almost all ties back to economic precarity. Specifically, concentrated poverty and relative deprivation.9

Concentrated disadvantage pushes poverty into segregated communities, making it very difficult for those areas to attract investment and economic opportunity. A great deal of network analysis demonstrates that the incidence of violent crime in most cities is concentrated in a few local neighborhoods. That’s why someone like me can visit Chicago with little concern for my safety. The areas of the city in which I’m likely to travel are perfectly safe.

Chicago is also a great place to experience a phenomenon called relative deprivation. Relative deprivation looks at poverty in comparative terms to other communities and individuals nearby. It’s one thing to be poor in a rural region, surrounded by other rural regions that are just as poor. In a city like Chicago, on the other hand, a short train ride will bring you from fabulous wealth to wretched poverty all on the same track. Someone in an impoverished community in Chicago can see all around him the great wealth that is available…just not to him.

Every other explanation is tangential to the ills of concentrated poverty. Loss of investment in economically segregated communities means the streets degrade, buildings cannot be maintained, infrastructure decays. It becomes clear to those living in these communities that they do not matter to the larger society. This leads some to question why they should adhere to the norms and values of a society that throws them away. Many such communities are also considered food and health care deserts.

A great deal of recent research has also been done on the physiological and psychological impacts of poverty on individuals. According to the American Psychological Association, “In addition, low-income children are at greater risk than higher-income children for a range of cognitive, emotional, and health-related problems, including detrimental effects on executive functioning, below average academic achievement, poor social emotional functioning, developmental delays, behavioral problems, asthma, inadequate nutrition, low birth weight, and higher rates of pneumonia.”

Then add racism on top of this, the kind of racism demonstrated by sending masked terror squads empowered by the Supreme Court and the President of the United States to discriminate against people of color, and we compound the physiological and psychological consequences. According to the National Library of Medicine, “…exposure to racism severely and negatively impacts the health of people from minoritized ethnic groups…”

These impacts on mental and emotional health are clear contributors to the increased likelihood that a child born under these conditions will experience domestic and street level violence. Many children in poor, minority communities witness or experience this violence from the police. We have plenty of video of brutal acts of violence committed by ICE and associated local police under their auspice. What impact does this have on the probability of increased violence in targeted communities?

Adding the Military and Paramilitary Forces to the Mix

When confronting those who support the use of the military in fighting crime in urban centers, even using urban centers as a training ground for the military as proposed by the President, there is only one question. How is such an investment in money and manpower going to address the underlying causes of crime? In fact, an evaluation of this strategy should lead us to hypothesize that this military solution can only serve to make things worse.

We can test some hypotheses in real time.

Hypothesis 1: {The Null Hypothesis) Sending in the military and paramilitary forces will have no impact on crime.

Hypothesis 2: Sending in the military and paramilitary forces will temporarily reduce crime, but crime will return to previous levels once the military and paramilitary forces are removed.

Hypothesis 3: Sending in the military and paramilitary forces will temporarily reduce crime, but will contribute to increased crime once removed.

The argument in support of Hypothesis 3 is as follows. If lack of economic opportunity and concentrated poverty is a causal factor in crime, then the presence of militarized forces in these communities will make matters worse. Armed soldiers in the streets will very likely encourage people in that community to remain in their homes and not participate in the economic activities they otherwise would, causing a negative impact on legitimate economic networks. Further, any economic activity that may have come from outside the community, bringing even limited capital, is also likely to be discouraged. Thus, the economic situation of the community is further eroded.10

Militarized forces in the community will also increase the reality and the perception of social isolation and stigmatization. Here billions of dollars are being spent on soldiers and weapons and armored vehicles. Nothing is being spent on food, healthcare or education. All around, members of the community are reminded that they don’t belong to the larger society, increasing the likelihood that some will decide that the norms and values of the larger society do not apply to them. A militarized presence, contrary to what the President and his minions suggest, will contribute to further social disorganization.

Furthermore, at least some of the militarized personnel will abuse their power and status by inflicting unnecessary violence11 on members of the community. We have more young people exposed to legitimized violence. More stress on the streets contributes to increased probability of domestic and street level violence. This will increase the probability that some in these communities will understand violence as a legitimate means of getting what they want.

Under these conditions we are also degrading, in many communities we are further degrading, the perception that the police are a legitimate authority. The relationship between the police and poor communities of color is already challenged, to say the least. We know that when the community does not trust the police, they are unlikely to go to the police to deal with interpersonal conflicts. They are more likely to take matters into their own hands, increasing the likelihood of violence. They are also less likely to turn to the police if victimized, increasing the pool of potential victims of violence.

Also, the presence of militarized police ironically increases the value of many illegal activities such as drug dealing. Increasing the risk increases the profit potential for drug dealers who can bypass increased enforcement and thus increases the incentive to do so. Criminal networks will certainly find workarounds to the inconvenience of a militarized force if given enough time.

Furthermore, most violent crime is not intentional or rather planned. Most violent crime happens because of mishandled interpersonal conflicts. A militarized force will have negligible impact on this kind of violence because at the point of conflict the participants are not taking them into consideration. In fact, the participants often do not take much into consideration. They are lashing out in anger or fear. Perhaps an increased presence may be able to intervene before such conflicts get out of hand, but most military and paramilitary forces lack the kind of training and expertise that local police have developed over time.

In the long run, I believe Hypothesis 3 will prove prescient. Unfortunately, if that is the case, that offers an argument on the part of right-wing propagandists to claim that a military presence must be made permanent. If crime goes down temporarily then rises once the military is removed, it creates the false impression that the military is a solution to crime. In fact, it exacerbates the variables causing the crime.

This is why we need to teach sociology.

Real Solutions

If you are really interested in solutions to crime, we already know what they are. It is just a matter of having the political will to engage them. We already have the money. As you will see, some of the solutions are not even particularly expensive.

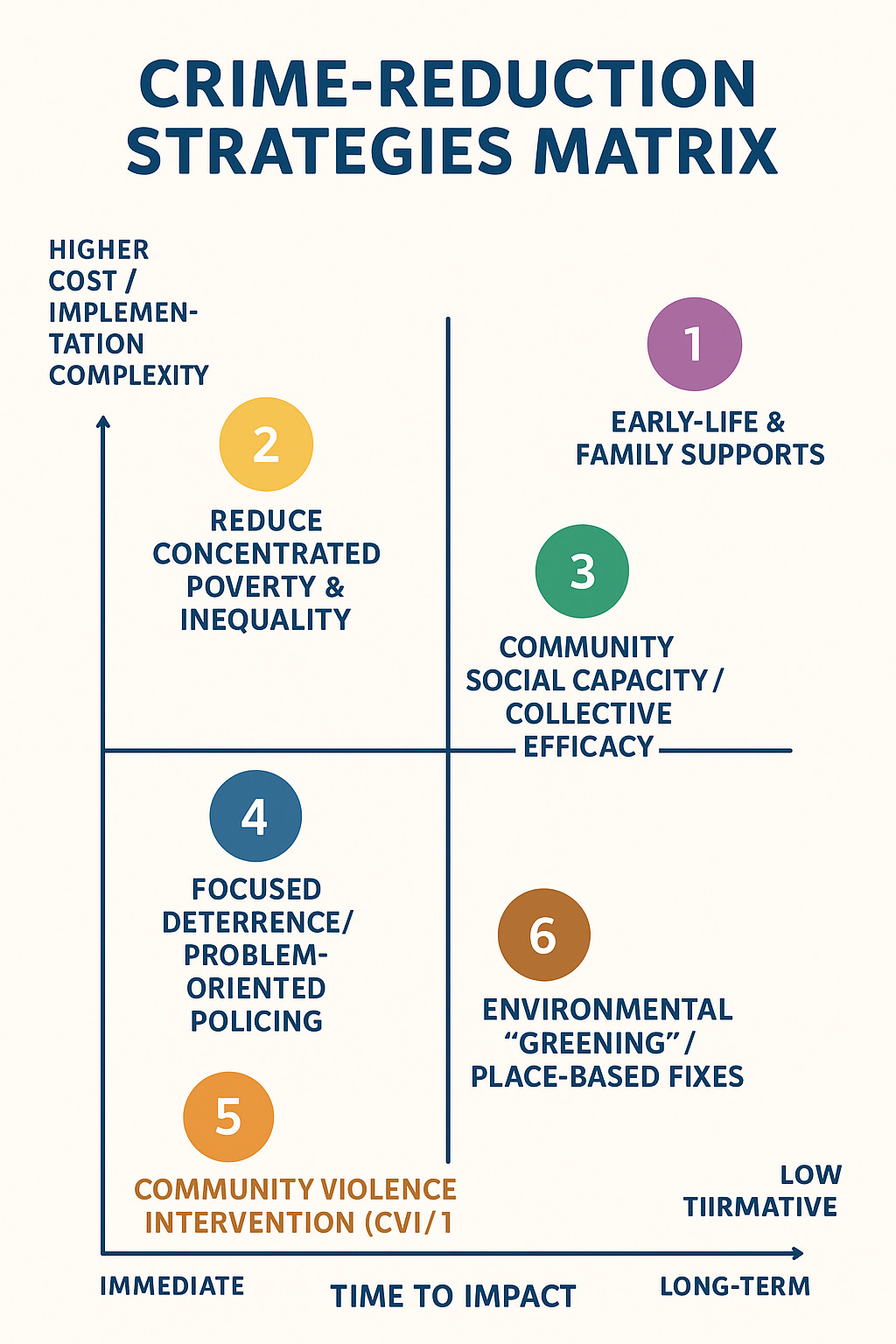

If your thesis is that crime is linked to poverty, the most obvious solution is to reduce poverty, or at the very least the impacts of poverty. This starts with investments in social safety nets. Making sure that people, regardless of income, can meet their needs. It means investing in education, child-care, and health care in these communities. Of course, this is exactly the opposite of what conservatives and the political right in the United States advocate.

Because it is very difficult to convince businesses to invest capital in communities of concentrated poverty, government interventions are necessary. Investments, whether they are private or public, must be made in housing and infrastructure to ensure that people are living in accordance with an advanced modern society. In doing so, it becomes easier to convince more financially secure working- and middle-class people to live in and to invest in these communities.12

Investments in the larger region are also necessary. Mixed-income housing is a powerful strategy for rescuing people from the consequences of concentrated poverty. Families that can live in middle-class communities have access to middle-class resources and often conform to middle-class norms and values.

Family and community childcare and violence intervention is also key, assuming these programs have enough resources to do the jobs they are assigned to do. This can include family planning, parenting courses, mental health resources, job retraining, nutrition programs, books and libraries, education programs, housing for the homeless. These supports are necessary and effective when their missions are clear, and they are adequately funded and professionally staffed.

And, yes, there is a role for the police. Targeted community policing has been shown to be an effective deterrent and intervention for crime. This only works, however, when the police act as partners with members of the local community. In many cases, it takes a great deal of time and effort to build the trust necessary to maximize such strategies. When police and members of the community are engaged in a decades long conflict cycle, it is hard to intervene.

Even simple measures like community greening, turning vacant lots into community gardens, parks, and green space has demonstrated a notable impact on crime. Such projects create healthier environments and demonstrate that the lives of those living in the community matter. I mean, can you think of a more opposite response to right-wing tough on crime policies than planting grass and trees in areas of concentrated poverty and crime?

This essay is long enough only to touch the surface of the issue of crime. Countless volumes of research have been written. Each volume contradicts the right-wing notion that all we need is more brutal men with big weapons to get a handle on the “hoods” that are causing all the trouble in these communities.

In fact, all of the research indicates that crime is a response to deprivation, mostly but not exclusively economic deprivation. Any legitimate debate on crime must begin with that.

These psychopaths were invariably represented as young men of color, referred to by Hillary Clinton as “super-predators.”

Explanations range from improved policing to decreased lead exposure, and demographic shifts. Some suggest that increased incarceration was a factor, but this doesn’t explain why violent crime levelled off while incarceration rates increased. The bottom line is that there was a convergence of factors that caused the crime wave, and a convergence of factors that ended it.

The hero of the Death Wish movies.

To be fair, some cities are experiencing high crime rates, even if those rates are trending down.

Balko, Radley. 2013. Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces. New York: PublicAffairs.

Durkheim, Émile. 1964. The Division of Labor in Society. New York: Free Press.

This is called Strain Theory and was posited by sociologist Robert Merton. He proposed that society provides legitimate goals for everyone, the values, but access to the legitimate means of achieving these goals is not accessible to everyone. This creates differential responses, or strain. Those who accept the legitimate goals and means for achieving these goals are “Conformists.” Those who accept the goals, but reject the means are your “Innovators.” This group includes your criminal element, gangs, drug dealers, pimps, etc. Those who reject the goals but are willing to play along with the means are called “Ritualists,” while those who reject both the goals and means are “Retreatists” often hobos, hermits and recluses. Then there are the dangerous “Rebels” who seek to change the goals and means.

There are many reasons to focus on violent rather than property crime. First, when people think “crime” they are often thinking about violent crime. Secondly, violent crime is more likely to be reported, therefore, the data is more valid than that for property crime.

Key citations (representative meta-analyses & syntheses I used)

Hsieh, C.-C. & Pugh, M. D. — Poverty, income inequality, and violent crime: a meta-analysis (classic meta). Office of Justice Programs

Nivette, A. et al. — Cross-national predictors of crime: A meta-analysis / cross-national syntheses. SAGE Journals+1

Jacobs, L. A. et al. — Meta-analysis of neighborhood effects on recidivism / neighborhood risk factors. (2020–2022). SAGE Journals+1

Matias et al. — Intimate partner homicide: A meta-analysis of risk factors. (2019/2020). ScienceDirect

Braga, A. A. et al. — Updated systematic review on disorder policing and broken windows interventions (2024). Crime and Justice Policy Lab

Pazzona (2024) — recent re-examination of inequality & crime relationships. ScienceDirect

Annual Review / Global Study on Homicide syntheses (2023 and UNODC summaries) for cross-national homicide drivers. Annual Reviews+1

Let’s leave aside for now the legitimate debate on what constitutes “necessary violence.”

There are some negative consequences of this strategy as we can see from the phenomenon of gentrification. Systems will have to be in place to protect long term members of the community from the negative impacts of rising property values.